Anyone who knows me would know I’m telling the truth when I say I’m a technology enthusiast. I ditched my analog watch for the original Apple Watch back in 2015, and these days I rarely leave my house without my Apple Watch Ultra gracing my wrist (in all of its bulky glory). I came of age in the era of music and video streaming services, so I never had a CD or DVD collection of my own. A lot of my reading was done on my Nook, and later my iPad; my writing has always been at a keyboard. My photography on a cell phone. We live in a world dominated by the digital, unable to touch or see and owning almost nothing of the intangible digital items we consume. As a result, we have entered an era I like to call “the Revenge of the Analog.”

My analog journey started with my coffee maker. I grew up on the Keurig at my parents’, and have been a coffeeholic since I was just starting high school, so when I left for undergrad I decided it was time to upgrade my coffee setup. After looking into the process that could yield me the optimal cup of coffee, I invested into pour over. I soon cherished the time I spent with my Chemex and gooseneck kettle, and the coffee-making experience became a vital piece of my morning ritual.

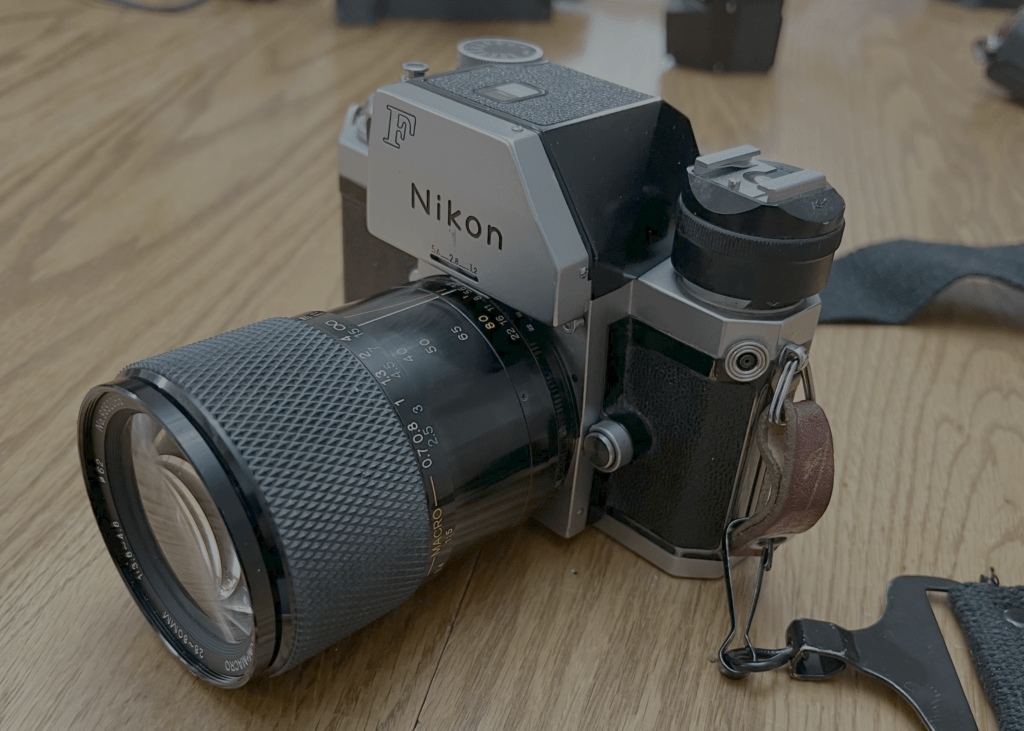

In college, one of my roommates had inherited his dad’s vinyl collection. He would collect newly-pressed records of his own, and when we moved into our first apartment he set up his record player and speaker system in the living room, often playing his new finds for our guests. My own vinyl collection began when we visited a record store together, and I eventually bought a record player and powered speakers when we moved out of our shared apartment. For one of the first times in my life, I actually owned an album I liked instead of paying Spotify for the pleasure of listening to it. Around the same time, my grandpa gifted me his Nikon F, Nikon’s first SLR camera; he bought it in the 60s, and it was his first “nice” camera he ever owned. A budding amateur photographer, I was thrilled to learn how to use it, and would travel with my buddy who was a film photography enthusiast to try out different brands of film.

Reflecting on these experiences now, I think I’ve been chasing the intimacy that comes with using pieces of analog technology. I loved fiddling with the shutter speed on a camera to get the exposure just right, or setting the needle on the record and watching it run in the grooves, hearing how the information visibly encoded on it becomes a delightful melody. The convenience and versatility of the digital is unparalleled, but when I open the Camera app on my phone and snap a picture (or 100 pictures, since I’m not limited to just 36), it hardly feels as satisfying.

We are collectively entering an era that will be and already is dominated by “AI.” Generative AI can artificially generate photos and videos that are convincing enough to be mistaken for the real thing. It can produce music that, if played in the background of a doctor’s office or mixed into a playlist, would be indistinguishable from a human creation. It can even convincingly mimic human interactions online to such a degree that it is becoming much more difficult to detect who is a “bot” and who is not. It is not a stretch to think that, within a very short amount of time, much of the digital content we consume will have been created wholly by generative AI. Such content could be optimized to be the most attractive to click on; it could be the most earworm-y music, the most breathtaking “photograph,” the most shocking video, or the most rage-inducing social media post. What do we do when online content becomes AI slop? We move offline.

For reasons that likely resonate with my own, vinyl has become quite fashionable, and my local film lab has become busier and busier with new customers over the last couple of years. Live music gigs are still on a downturn, but we may soon be living in a world where live music becomes proof of authenticity, and where art galleries become curators of authentic human expression. To be sure, this world would be worse than our pre-AI existence; genuine artistic creation would be inaccessible to a great number of people because of physical or economic constraints. However, a more analog human experience could place us back into control over how we spend our time and attention, and could allow us to tear down our digital walls and spend more time physically present together, appreciating the true beauty and creative expression of humanity together, as we once have. Perhaps this is all wishful thinking, and perhaps the digital world we have built will come to be reinforced more throughly by emerging concepts like the Metaverse; maybe our inborn desire for human connection could be satisfied by seeing our friend’s VR avatar as we float through a digital art gallery. Personally, I find this version of our shared future revolting.

While I am not likely to abandon my Apple Watch, my smartphone, or my social media consumption habits anytime soon, I do want to continue to chase the intimacy of analog experiences. I want to continue dialing in my perfect brew, testing new cameras, and collecting new records. My hope is that, as the use cases for nascent technologies like AI and VR become apparent, we collectively decide to embrace human authenticity and carve out spaces in our digital lives that exclude, to the best of our ability, the soulless impersonators that will become more and more a part of our daily lives.

Leave a Reply